In four chapters, author Geoff Mayer dives deep into the meaning and the many faces of the melodrama, highlighting several aspects and decades that made audiences familiar with the endless confrontation of virtue against reckless action, true love against intrigue or simply “good” versus “bad” characters, parties or companies.

Here we learn about the main film varieties that featured melodrama plots, naturally also present in the two most American movie genres, namely the western and film noir. And how the propaganda films after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Fu Manchu serials, combat films and the melodrama easily went hand in hand in the 1940s.

Here we learn about the main film varieties that featured melodrama plots, naturally also present in the two most American movie genres, namely the western and film noir. And how the propaganda films after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Fu Manchu serials, combat films and the melodrama easily went hand in hand in the 1940s.

Because the “genre-generation machine,” melodrama, is the foundation and the main direction of American cinema, Mayer says. Apart from basically moral markers that simplify the nature of each character in movies of that sort, culture is the other chief identifier that makes this study so interesting.

As the “specific values embedded in notions of good and evil are determined by the culture and they shift from nation to nation, from region to region and from period to period. Above all else, melodrama reassures that the world has meaning….”

By closely surveying the kind of moral clashes that changed from the 1920s to the 1950s (and their respective characters, types, representatives, heroes and villains) in the movie productions of the periods, changes in the American cultural values system and society as a whole become very visible. Audiences, apart from being entertained in the theater, also were challenged to act as “a jury” and to be engaged emotionally, as this sort of obligation may have been another reason to go to the movies and witness justice taken care of in the melodrama. (For example, several more sophisticated A western productions of the 1930s were directed at audiences from the metropolitan areas, while at the same time countless serial B westerns were delivered to audiences in rural areas, supporting role models and moral standards believed to be more common there.)

Chapters one and two are devoted to the “sensational melodrama” that deals with extravaganza, high emotion, and dance and performance parts; it is built on very basic and reduced plots and characters who are caught in a clearly visible “clash between good and evil.” The early American western is a main genre in those two sections. These films often had a populist agenda, in this case clearly supporting the small businessman, farmer or worker and identifying as their ultimate antagonists the big corporations, intrusive governments, tax agents, banks, or the corrupt sheriff. Out of the more than 1,000 westerns that were shot in the 1930s alone, Meyer selects several dozens that were either very typical or impressed by important variations, and he makes his point about changing moral values in comparing miscellaneous versions of the Wyatt Earp tales, RKO’s many westerns, and the occasional films where civilizations (rural vs. big city) clash and result in western comedies. Serial queens, gentlemen detectives and war heroes are also introduced.

A somewhat modified type of melodrama, also very popular in the 1930s, is featured in chapter three. The “melodrama of passion,” or “drawing room drama” had the focus more on feminine emotion, love stories, and passion. Action, shootouts, or spectacular chases were usually not part of such movies. In this close look at the variations, Meyer specifically takes up W. Somerset Maugham stories, namely “Miss Thompson” and “The Letter,” and the various film versions over the decades. This is most intriguing, as several aspects as well as the stories were massively altered, depending on the year of production.

With the focus on human behavior and disappointment that follows trust in the wrong people who have very different ideas about morals, virtue and ethics in American movies, it is only natural that the melodrama is probably very comfortably at home in films noir of the 1940s and 1950s. Hence the most comprehensive and also best chapter here is the fourth one, “Film Noir, Virtue, the Abyss and Nothingness.” On the last almost 150 pages, Meyer, who has published extensively about film noir before, establishes his ideas about the style, namely that it rather often represented a shift in melodrama and not solely left protagonists speechless and trapped in a world without meaning. Instead, he argues that a shift towards Gothic elements and finally tragedy were added to the melodrama, and then, in many cases, the style also had “virtue drained of its moral significance…”

To prove his case, he singles out popular noirs such as Double Indemnity, The Maltese Falcon (all versions), The Seventh Victim, Framed, Human Desire, Gilda, different version of The Glass Key, Murder, My Sweet, Ride the Pink Horse, Out of the Past, Angel Face, and several other classics.

Mayer, apart from describing the mechanisms of the melodrama in cinematic terms, in Hollywood’s Melodramatic Imagination also contributes sketches of a moral compass that was exploited in films at specific times for designated audiences; that allows to draw conclusions about the shifting ethical standards in American society.

A valuable addition to any book collection on American movies, especially early westerns and film noir. The over-sized paperback comes with six pages of color film posters and 100+ sepia film stills and movie ads.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2022

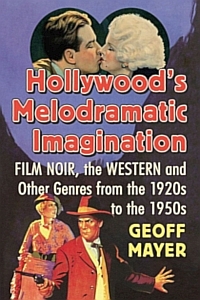

Geoff Mayer. Hollywood’s Melodramatic Imagination: Film Noir, the Western and Other Genres from the 1920s to the 1950s. McFarland, 2022, 365 p.