Maybe one of the reasons why actor Robert Mitchum looked so comfortable and at home in western movies, was the fact that he bred horses, preferred the casual cowboy outfit off the film set, and seemingly simply played himself, whenever he took the part of the cowboy, the Sheriff, the outlaw or the weather-beaten stranger who attracted trouble like a magnet.

Robert Mitchum (1917-1997) was a very busy actor, starring in more than 100 pictures, about a third of those were westerns. His career lasted for more than 50 years. It is not easy to sum up his entire western output, since he played a number of different characters, although mostly the loner, the laconic drifter, the quiet lawman or man on the run.

Robert Mitchum (1917-1997) was a very busy actor, starring in more than 100 pictures, about a third of those were westerns. His career lasted for more than 50 years. It is not easy to sum up his entire western output, since he played a number of different characters, although mostly the loner, the laconic drifter, the quiet lawman or man on the run.

A setting in Mexico also proved to fit him and his roles, as he starred in many productions that had a Mexican/American cast, that were shot during the high-time of the Good Neighbor Policy. No matter what western role he played, he proved to be the cynical, masculine, often bitter, but always cool variation of the character required by directors.

These roles had a lot in common with the person Mitchum, who, in real life, was more or less the same person who didn’t really care about conventions and American hypocrisy lurking around every corner in the 1950s.

“He drank his fill and was often pleasantly stoned on marijuana reefer, yet he rarely missed work because of it. He claimed he didn’t care about the artistic merit of his projects but was always letter perfect on set, even in potboilers that were several rungs beneath his talents. He effortlessly sang and recorded calypso, folk and country-western music, punched out heavyweight boxing contenders, served time in jail, and bucked every convention of the Hollywood system while claiming he didn’t give a damn about anything.”

His stoicism and natural coolness were the perfect ground on which any new western movie role would grow and result in most realistic characterizations of men of the old west. An attitude, that also came in handy for his many parts in classical films noir.

And those two genres overlapped, as there are so many westerns with film noir characteristics (mostly done by RKO), so that the sub genre of noir westerns was (posthumously) created by film scholars. “By the end of World War II, westerns themselves were becoming more psychologically complex and Mitchum understood these themes. Hollywood choose him to be their darkest star.”

As leading actor, he was responsible for turning the westerns Pursued (1947) and Blood on the Moon (1948) into film noir masterpieces. As a performer who said that he was just around to get the job done, he was one of the very few Hollywood stars who easily agreed to play the bad, dark and sinister type. And would not worry about consequences or a ceasing public interest that could mean fewer job offers.

He started out as an extra in the 1943 Hopalong Cassidy movie Border Patrol, followed by eight more films for the outfit that same year (as the B movies of that sort usually were shot in just a few weeks). As he impressed several directors and producers, he very quickly moved on to bigger (and better paid) jobs.

After a few years in the business, classic westerns such as River of No Return, El Dorado, The Way West, 5 Card Stud and (much later) Tombstone followed, while he also starred in a number of still underrated films, for example in Man With the Gun from 1955. Mitchum received a Western Heritage award posthumously from The National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum (formerly Cowboy Hall of Fame) in 2013. He absolutely deserved it.

Author Gene Freese, a screenwriter from Arizona, took great care in documenting each of Mitchum’s westerns, and that includes comments, articles and interviews from all sorts of sources, such as movie trade papers, Hollywood gossip, interviews with stuntmen, directors, former sidekicks and famous film partners. Each movie is presented meticulously with setting, cast, crew, filming locations, stand-ins, stuntmen, fight choreography, musical content and press reviews on several pages; 80 black-and-white photos show the actor on sets and private.

As Mitchum was busiest from the 1940s to the 1970s, this period receives more than 160 pages. A time of fewer productions followed, when he spent most of his time tending to his various horse ranches, as he seamlessly changed between cowboy characters and a strong love and devotion for horses in private. He became an authority on quarter horses and loved the country life.

When he became more closely involved with Hollywood again in the 1990s for just a handful of films (he turned down many books as he did not like the modern roles that were offered to him), he mostly represented the well-aged veteran cowboy type, often playing the anti-hero. The great actor died in 1997 of emphysema and lung cancer (just one day before fellow western Golden Age superstar James Stewart).

Mitchum’s life and westerns are splendidly portrayed here, with a strong emphasis on his character and devotion to horses and the cowboy way of life, with or without a camera around.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2020

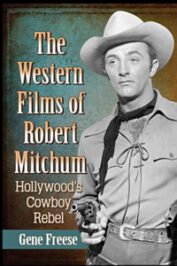

Gene Freese. The Western Films of Robert Mitchum. Hollywood’s Cowboy Rebel. McFarland, 2020, 244 p.