The small-screen world of the short musical film, a form of media presentation usually associated with coin-operated cinematic machines of the 1940s and later decades, keeps fascinating historians, media researchers, music experts and sociologists.

Even if nowadays media, video clips, music in all variations and formats, and modes of presentation are easily available on a laptop, cell phone or streaming device. Naturally, the way we appreciate the recorded video today has to with what those pioneering machines, and their inventors stared as early as 1940.

Even if nowadays media, video clips, music in all variations and formats, and modes of presentation are easily available on a laptop, cell phone or streaming device. Naturally, the way we appreciate the recorded video today has to with what those pioneering machines, and their inventors stared as early as 1940.

So looking back on the 1990s, MTV with the mass of music videos was definitely a game changer in terms of media distribution and affiliated music sales. Even so, the platform did not start massive music media consumption. It continued what small-screen machines and musical clips professionally arranged, performed, filmed and recorded kick started in the 1940s.

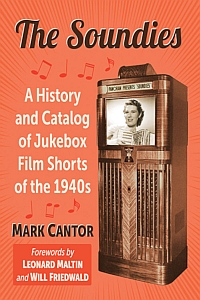

The emphasis of the huge history at hand is on the very pioneer type of music clip, namely “the Soundie.” This distinct name refers to a three-minute musical film “copyrighted and distributed by the Soundies Distributing Corporation of America (SDCA), a subsidiary of the Mills Novelty Company, for display in the Mills Panoram machine.”

The Panoram for roughly seven years (until 1947) would be the small and cheap entertainment sensation that provided music and dance performances for millions of “audiences” in the US without going to a theater or cinema. It had a small screen in the upper part of the heavy wood chassis and was equipped with several speakers for better volume. Although the experience of quickly enjoying recorded music in public places, bars, restaurants or waiting areas was not new, as Americans were familiar with jukeboxes since the early 1930s, the Panoram became a success. As listening and watching your favorite artists, bands and dance ensembles was unmatched. Even it was a bit expensive as each musical journey would cost 10 cents, that would allow you two titles on your jukebox, buy a hamburger or a loaf of bread at the time the Panoram was introduced to the public in 1940.

Author Mark Cantor, historian, jazz fan, musicologist, and famous collector of early jazz films from Los Angeles completed this impressive catalog of roughly 1,900 Soundies (altogether, some 2,600 clips are mentioned here, not all are “real” Soundies.) He lists all personnel, musicians, dancers, arrangers, trade reviews, recording dates and locations and all kinds of trivia related to the respective set and song version. His catalog is breathtaking, and to guide the reader through the mass of recordings, the first 130 large-scale pages of volume one are devoted to the history, antecedents, production and esthetics of the Soundies. That is, 130 large 8.5 x 11 pages, as the catalog is immense.

The other 270 pages of the first volume are reserved for the movie entries, continued in volume 2. It comes with several appendices, among them bibliographies, including a Techniprocess (the hardware development) and Featurettes (an important Soundies producer that used L.A. talent) index, and a thematic index. The volumes can be searched for 80 thematic musical styles, locations or genres. Those extras are priceless, as the 1940s were a most productive and inventive decade in American history as musical styles, and their regional developments (and preservation) are concerned.

The Soundies could feature any style from jazz to pop, explains renowned music writer Will Friedwald, in one of the two forewords of the volumes. “Soundies turned out to be an invaluable resource, particularly in documenting those performers Hollywood had otherwise excluded from theatrical features and even shorts. African American bands, singers, and dancers, female instrumentalists, country and western groups, early R & B acts and others undeserved by the mainstream movie industry … At the same time, many future movie stars turned up on screen … Alan Ladd, … Liberace, Doris Day … debuted as Soundies artists.”

The coin, once inserted into the Panoram, started a reel with altogether eight musical clips, no selection was possible; one could not play a certain tune again. However, there was enough variation as the reel would be changed every week. The extreme efforts to offer an entirely new film reel every seven days nationwide, with eight fresh songs by other artists, filmed and edited was very challenging.

After all, in the WWII years, unusual production conditions made production and distribution difficult, as musicians, arrangers, composers, or dancers could be drafted into service any time. In addition, in 1942 the American Federation of Musicians began a strike that lasted until 1944 to ensure members better terms with recording companies. As a result, many Soundies of that time featured non-union personnel, mostly unknown talent that very often would dance and sing to a prerecorded playback record of an entirely different band, sometimes a band of union members.

Anything necessary to come up with the new eight clips reel was done under extreme pressure, besides filming and editing on a budget. More than fifty companies (among them Minoco Productions, Cameo Productions, R.C.M. Productions, and others, mostly from the L.A. area, that offered footage ranging from highly professional to low-budget material) provided film and audio to the SDCA.

Apart from being great entertainment, those clip often remain the only evidence and recording of particular artists, who never went in the studio or on tour. And they serve as important documents to see how one performer’s style changed over the decades. Simultaneously, the films inform about contemporary musical tastes, what basics were expected to be included, and how a concert, a show, a performance was conceived and produced on short notice. And how censorship was avoided: dozens of production files, contracts, and internal communication deal with that problem.

Furthermore, the 125 pictures in the volumes that include many Panoram ads, commercial posters and film set shots will let readers experience the Soundies and their genesis first hand. The texts, photographs (and films) equally report how stereotypes, gender roles, racist strategies going back to vaudeville days and other atrocities were a common thing in show biz and performances of the day.

The two volumes of The Soundies: A History and Catalog of Jukebox Film Shorts of the 1940s also include 75 (short) interviews with directors, performers, set directors, choreographers and staff who participated in one way or another in filming or distributing the recordings.

The Soundies still are around, on Youtube and even on old VHS tapes. And as a special treat, many of them are preserved on the author’s website at www.jazz-on-film.com for enjoyment and as audiovisual addition to the two volumes.

Mark Cantor has provided a monumental catalog, five decades in the making, and a complete history of the Soundies and anything related to that media; absolutely stunning!

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2023

Mark Cantor. The Soundies: A History and Catalog of Jukebox Film Shorts of the 1940s. Vol. 1 and 2. McFarland, 2023, 893 p.