For many centuries stories, tales, parables and myths not only have been sources of inspiration or simple methods of entertainment; those creations were models to live and judge by and inspirations of how to react in certain situations (as well as guidelines of how not to).

Tales and stories told over and over again finally found their place in the legacies and histories of cultures and people. Consequently, they were easily recognized, sometimes altered to fit present needs and reactivated. Ultimately, a popular culture of individual countries or cultural areas crossing entire continents developed and ,hence, became the vault for new tales and stories.

Tales and stories told over and over again finally found their place in the legacies and histories of cultures and people. Consequently, they were easily recognized, sometimes altered to fit present needs and reactivated. Ultimately, a popular culture of individual countries or cultural areas crossing entire continents developed and ,hence, became the vault for new tales and stories.

Today we find moral guidelines, instructions, lessons on life and examples of favored themes in other media called novels, movies, TV series or computer games.

A similar development can be discovered when researching the origins and antecedents of constitutional thought or political theory, which was also manifested as an important part of a story, poetry, history, song or myth. Actually, many myths start with a quest or an event of times long past when a necessity to alter or readjust doings and results of villains, or let us call them political enemies, arose.

In the myths then both sides declare their motivation and actions, leading occasionally to battle or sometimes to philosophical dialog and in the end a forerunner of political theory in a tribe, country or a particular society.

The strong dialog that ,by now, takes place between both popular culture, modern myth and political theory is easily traced in (basically entertaining) productions that work as manifestations of political ideas which for the contemporary consumer are forever connected with fictional characters of TV series and movies.

“We may not directly invoke Thomas Hobbes … when we read of the troubles of Katniss Everdeen and Peeta Mallark in … The Hunger Games. Whether or not we read Friedrich Nietzsche, we are presented with his arguments through the words of Valdemort, who tells Harry Potter … that “there is no good or evil, only power and those too weak to seek it.” … [W]e watch Platonic philosophy in Star Wars, Aristotelean theories of community and virtue in The Simpsons, Machiavellian approaches to power in The Godfather, and contemporary Marxism in … Avatar,” says Foy.

Now if you love The Simpsons the way I do, you will be pleased to find many essays on the nature of the state, political systems, virtue and the use and misuse of power, all represented by characters of today’s popular culture in this volume. I was particularly diverted by Evan Kreider’s essay on the comic book/graphic novel The Watchmen. More movies and TV series are subject to analysis such as The Office, Serenity and Firefly, The Incredibles, The Hobbit as well as the (American) action hero as a cultural myth and the image of women in TV series.

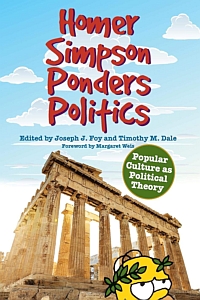

This title is the latest publication of a small series of books on the relationship of Homer Simpson (and fictional characters like him) and American Culture by editor Joseph J. Foy (Homer Simpson Goes to Washington: American Politics through Popular Culture (2008) and Homer Simpson Marches on Washington: Dissent through American Popular Culture (2010) by Foy and Timothy M. Dale.)

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2015

Timothy M. Dale and Joseph J. Foy (eds.). Homer Simpson Ponders Politics: Popular Culture as Political Theory. The University Press of Kentucky, 2013, 264 p.