The gialli (“the yellow ones”), introduced in Italy in the mid-1960s, are a film genre that combined all sorts of sensations, such as crimes planned and committed, detectives and amateur sleuths looking for clues, great landscapes, exotic venues, usually connected to airports and train stations, beautiful women, Gothic horror and disturbing soundtracks.

In the gialli, contrary to the standard crime or detective movie, the acts of killing, torture and presenting the victims of outrageous atrocities almost happen in a separate plot. At least, audiences may feel that way, as the camera takes on murder weapons, gloved hands, and terrified faces here are oddly long and detailed (although of course it all is part of the story).

In the gialli, contrary to the standard crime or detective movie, the acts of killing, torture and presenting the victims of outrageous atrocities almost happen in a separate plot. At least, audiences may feel that way, as the camera takes on murder weapons, gloved hands, and terrified faces here are oddly long and detailed (although of course it all is part of the story).

The mood, lighting, extreme and often psychedelic arrangements and visual effects make the solving of those crimes (almost always with a female victim) or the reconstruction of the killer’s motives matters of little importance. Usually, the meticulous preparation of the acts of capture, torture and killing – a feast for psychologists, anthropologists and therapists who could typify the kind of fictional characters in the plots, its directors and also the audiences that watch such violence happen – are in the foreground in the giallo movie.

Leaving the murderous, sadistic and incomprehensible preparations of the acts aside, the presentation, setting, and lighting of such scenes generally are highly aesthetic and often occur in a carefully prepared environment. Yes, there is a special elegance – even though usually conceived and carried out by insane and distressed personalities in the films – to it. “Long in length and filled with excessive baroquism, the murders are not just a plot point but a masterclass on the art of filmmaking.”

Not to mention the settings of many original Italian gialli, that lead us to ancient mansion, castles, palazzi that tell of faded wealth and power in impressive halls, gardens, dungeons or attics. Colors, especially deepest (blood) reds, may be most responsible for the gialli experience in cinemas. (Which leaves room to speculation if without the invention of color film, the genre would have been successful at all.)

Maybe not all original gialli were masterpieces. Some were simple, cheap, sensationalist films, featuring scantily-clad women and plots without surprises. Others, however, were exceptionally good. “Certainly, the giallo pivots between sexploitation and European psychedelia on the one hand, and avant-garde experimentation on the other, thus blurring the frontiers of what is considered art and what is considered cinematic sleaze.”

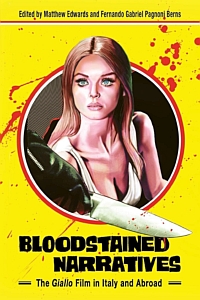

Bloodstained Narratives, edited by Matthew Edwards and Fernando Gabriel Pagnoni, in two parts explores some new findings in the classic gialli, before entering the major topic of the book: namely the various reincarnations of the giallo style worldwide. This is a rather unusual approach, as most titles on the style focus on the heyday of the films “usually shot and produced in Italy entirely.” In the fifteen chapters here, Italy, naturally, as the beginning of it all is present, but mostly the regional experiments with the style all over the world are in focus. Even though the gialli were never really gone, they lost audiences in the 1980s. This changed when only a few years later new generations of horror fans ardently bought the reissued films on DVD; and during the last few years, many (young) directors worldwide have presented their own versions of the contemporary giallo.

In part one, “New Readings on Classic Gialli,” we encounter texts on well-known artists and subjects in this context, such as cinematic eroticism, Mario Bava, Andrea Bianchi, Dario Argento, Jess Franco, actress Barbara Bouchet or colonial elements in film plots.

Editors Edwards and Pagnoni, together with thirteen other authors present a fine overview of the forces that created the originals and the recent international neo-giallo. Among the contributors are Lisa Haegele, Donald L. Anderson, Sean Woodward, and Sharon Jane Mee, to name but a few. Highlights here are interviews with directors Antonio Bido (“The Bloodstained Shadow”) and Romano Scavolini (“A White Dress For Marialé”) by Matthew Edwards.

The second part, however, “The Giallo Abroad. A Transnational Phenomenon,” is much more compelling. (Also because some information we find in part 1 already has been subject to analysis in other titles before, in one way or another – this varies from text to text.) This section leans towards the rarely discussed and analyzed gialli from Hong Kong, Canada, France, the US, and Japan. The films here then, read as gialli/neo-gialli, continue and extend the language, style and mood of the genre milestones. Some decades after the prime of the Italian gialli, the style resurfaced as slasher picture, horror film or psychological thriller. Nevertheless, the movies under inspection, even though adding several unique domestic elements, together with contemporary expressions of violence, voyeurism, eroticism and creeping danger, more or less openly refer to the classic genre pieces of the 1960s and 1970s.

The many links and connections shown by the authors come in very handy, as they reveal the numerous allusions to, quotes of and sometimes bold copies and mere theft of ideas taken from the originals that inform the current generation of films.

With Bloodstained Narratives, we get a useful update on neo-giallo with a transnational view and almost a manual for experiencing a new generation of genre pieces from various countries worth exploring.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2023

Matthew Edwards and Fernando Gabriel Pagnoni (eds.) Bloodstained Narratives: The Giallo Film in Italy and Abroad. University Press of Mississippi, 2023, 299 p.