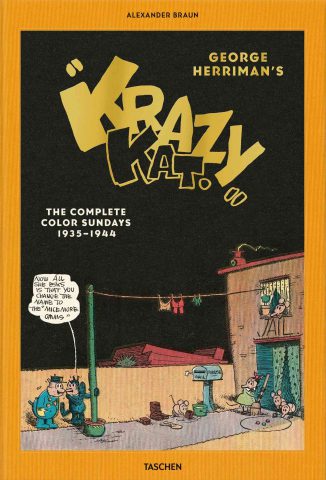

Once again, German comic book historian Alexander Braun has written a long text with lots of photographs, sketches and drawings that document a comic book superstar’s life and heritage.

George Herriman (1880 – 1944) the inventor of Krazy Kat is the subject of this mega book. His comic strip would become the first of many pet-cartoons to come in American popular culture, and it also revolutionized cartoon art itself.

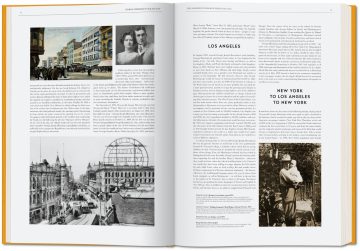

Herriman was born to Creole parents, and had white and black ancestry from New Orleans, which in 1910s America meant he would have grave difficulties finding employment in the larger cities. However, he successfully “passed” for white; in the early years of his career as an artist for various papers (either owned by tycoon William Randolph Hearst or his competitors) he invented a personal legend of being actually of Greek ancestry. (So he could explain his darker skin, and he started wearing a hat inside and outside to cover his curly dark hair.)

His concealed origin and the development of his main character, Krazy Kat, a black cat, gave way to many theories and politically charged interpretations when the contents and particularly the violence and lack of respect between (white) police, mouse and a (black) cat is analyzed. According to author Braun, this was never actually resolved and there are as many facts and theories that point to either a very critical observation of race relations with open racism towards African Americans (which, on the other hand, unfortunately was subject to probably many cartoons of the era) or a distant and rather musing view on black endurance or superiority in American society.

Herriman and his family moved between Los Angeles and New York, depending on his current employer. Before he eventually became successful, he experimented a lot with animal cartoons like the Dingbat Family and was probably best known in the early years of the 20th century for his cartoons on sports events.

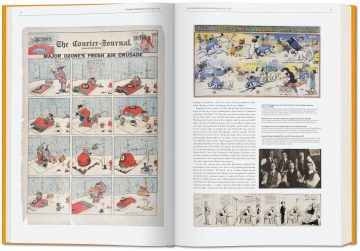

In 1912, newspaper owners decided to move their cartoons to a separate page that had no other news or articles; an important development within the genre. Herriman by then already had his regular strips in a Hearst publication and was one of the first cartoonists to benefit from that decision. Krazy Kat started in 1913 and ran until 1944, a very long time compared to the lives of most other newspaper cartoons, particularly those of the Sunday editions.

What made this strip such a special work of art, has to do with a number of reasons. Kat is not simply a funny character; he simultaneously represents many favorable traits as he is a caring, smart, street-wise, friendly, and diplomatic cartoon cat. Even though in a constant fight with rodents and cops, he still is an amiable fellow who never gives up and has a highly positive outlook, as he also is an expert in survival, organizing support of all kinds. Kat uses language that is a blend of colloquial English, neologisms, entirely wrong phonetic spelling and a laid-back style of casual talk, no matter who he speaks to. His nemesis, in a way, is Ignatz Mouse who tries to maim, torment or kill the Kat; so identifying the mouse as a metaphor for life under difficult circumstances would be a possible explanation, among others.

What makes this pet-relationship particularly strange is the fact that above all, Kat is in love with Ignatz and never understands complete rejection, even as it comes in the form of a brick from Ignatz that usually lands on Kat’s head. A famous running gag of the strip. The third pet in the story is Officer (dog) Pupp, a bulldog who gets involved in the strange relationship. He too, is a victim to various attacks and assaults of all kinds of (cartoon) violence.

Even if this sounds like a simple story line, the strips turn from uncomplicated and easy pet-fights to philosophical questions, discussions on life, the origins of things to most surreal, comedic and absurd plots; many of these have no real ending or conclusion.

This is the point where Herriman’s art gets most interesting, as at that time hardly anybody else made this the topic of a cartoon (except for Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo.)

Furthermore, Herriman’s comic strip panels were no longer rectangular and of identical size. Already around 1916 his panels were wide, could take over half a page and presented more of everything: action, background, landscape and detail. As he was also a fan of the American desert, Monument Valley and Navajo art, he designed numerous panels in the shape of Navajo patterns.

And he went much further, as Hearst in whose papers he was printed, understood that Herriman did break new grounds and never stopped him from experimenting. Some Krazy Kat stories switched between violent action in one strip, but then let the protagonists simply give small allusions to possible actions that were never carried out in another; and let the reader finish those, solve phonetic or philosophical riddles and continue the strip by themselves. Or in strips all panel borders and backgrounds were removed or just mixed up completely, and suddenly have collages of drawings and photographs. These very modern ideas appeared simultaneously in many other forms of modern art worldwide like Dada, Surrealism, or experimental art.

This is worth mentioning, as comic art and cartoons in the first half of the 20th century were miles away from being seriously called art by anybody. Unfortunately, not all readers liked or understood Herriman’s ideas, and the strip was not always popular; although it was admired by artists and academics. It also is a very early example of unusual gender roles, as Ignatz (married to Minnie) and Krazy Kat are male characters; Kat is the first queer cartoon character ever.

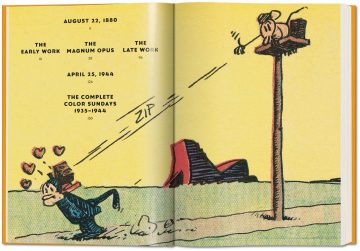

Alexander Braun’s 100-pages text gives many more details and goes deeply into more information on drawing, marketing, Krazy Kat in the movies and other parts of the too short life of Herriman.

The title contains all Krazy Kat color stories from 1935–1944 in XXL format in great quality. So it comes as a Taschen heavyweight, the 630 pages end up with more than 14 pounds, and a cardboard carrying case protects the beautiful print on heavy paper that measures 14 x 20 inches.

A well-documented and carefully done edition on one of the most important innovators and visionary comic strip artists of the very early 20th century.

The book is available in three individual editions (French, English and German.)

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2019

Alexander Braun (ed.) George Herriman’s “Krazy Kat”. The Complete Color Sundays 1935–1944. Taschen, 2019, 632 p., ISBN 978-3-8365-6636-0 (English)